One Fish, Two Fish… These Books are Racist?

Childhood favorites revisited and seen in a different light.

Dr. Seuss: a big part of many of our childhoods. With his books’ familiar rhymes and fantastical illustrations, they’re a staple for young kids – and a major throwback for many adults. There’s proof of it too, as Seuss’s books (“The Cat in the Hat”, “One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish”, “Green Eggs and Ham”, “Oh, the Places You’ll Go!”, “Fox in Socks”, and “Dr. Seuss’s ABC”) take up six of the top ten spots in USA TODAY’s Best-Selling Books, and placing thirty-three books out of one-hundred and fifty in the same list.

So what’s the problem? While Theodor Seuss Geisel, pseudonym Seuss, is often praised for his positive contributions to raising awareness about environmentalism, acceptance, and tolerance, his work has been increasingly criticized in recent years for its racist and insensitive imagery. Under scrutiny and an overdue review, Dr. Seuss Enterprises became aware of how Geisel’s work “portray[s] people in ways that are hurtful and wrong.” (Dr. Seuss Enterprises, 2021).

Six titles were removed from the shelves – none of them on USA TODAY’s Best-Selling Books list: “And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street”, “If I Ran the Zoo”, “McElligot’s Pool”, “On Beyond Zebra!”, “Scrambled Eggs Super!”, and “The Cat’s Quizzer”.

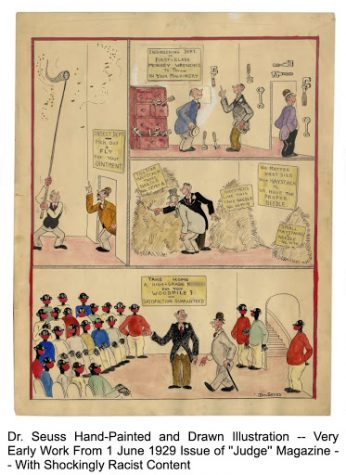

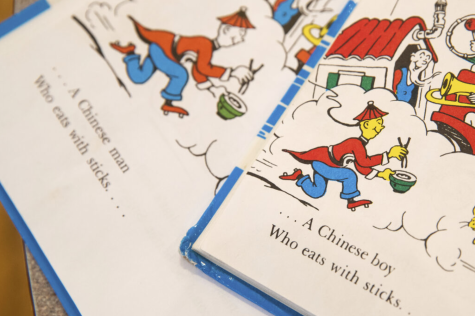

In “And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street”, a “Chinaman” is depicted with yellow skin, slanted eyes, a conical hat commonly worn in Japan, and is “eat[ing] with sticks”. Previously a political cartoonist, his discrimination didn’t stop at anti-Japanese agendas. He had a tendency to portray black people with a resemblance to monkeys, with overly large lips. One of his more appalling drawings from 1929 has blatant use of the N-word, the scene a depiction of “black people for sale.”

Keep in mind that “And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street” was written in the late 1930’s: there was a different cultural atmosphere then than there is now, and Seuss was able to see that for the most part. Shellie Cocking, chief of collections at the San Francisco Public Library and a former children’s librarian, reminds us, “…Dr. Seuss was someone who became aware of his use of stereotypes in his early work.” The illustration in “…Mulberry Street” was changed in 1984 to be without a ponytail and colored skin. The words changed from “Chinaman” to “a Chinese man” – but is that enough? Seuss never issued a personal apology, but his enterprise continues to make changes in his work as they see fit.

“Dr. Seuss was writing in the 30s,” said Suzanne Canady, an English teacher at Eaglecrest. “Not that that excuses racist attitudes, but we’ve evolved as a society and we’re more inclusive. We recognize more that there were problems with his books.” Like we’ve seen in recent years, sometimes it takes something big, terrible, and noticeably broken to bring awareness to the things we need to fix. The books aren’t being erased from existence, but they’re being taken off of the shelves. The importance of realizing intentional neglect has never been more prominent: history is there to be acknowledged, understood, and learned from.

“When you know better, you do better,” said Eaglecrest English teacher Kim Torpey. “We can’t teach our children to hide under a rock and not see the ugly truth.” So how will educators choose to move forward with these books? Seuss’s work, geared towards younger children, may install an inherent sense of stereotypes if not corrected by guiding adults. So wouldn’t it be more effective to teach young minds the good stuff first, not initially instill what we don’t want them to take after?

(Christopher Dolan, Associated Press)

“If they’re going to learn about being culturally responsive, if they’re going to learn about inclusion and equity, I feel like it needs to be done at that age in a more positive [way]. I think it needs to be a model of what to do and not to hit them with images of shame and what not to do, and how ugly our history is. I feel like kids need to be more emotionally intelligent to handle that,” says Torpey.

Being a part of many upbringings and having the ability to teach morals, it’s important that we look at these parts of influential literature as times change. “The Sneetches always resonated with me the most because it dealt with bullying and pride and things like that,” Canady reminisced. “I think Dr. Seuss’s books can be a launching point for those conversations that could give kids something to think about.”

Mistakes can be made, and in Seuss’s case, they aren’t always addressed immediately. But his work does prove to be something to be learned from – they’re a piece of history that shows that times can change, and they will, but only if we take action to make it happen.