Women of Color are Missing, and the Media Does Not Care

Missing white woman syndrome is a real thing in the media; too many women of color go missing without any news coverage to help find them. Why is this, and what is being done to change this?

At the moment, you can’t find many stories of the rising rates of women of color missing in the United States, with little to no conversation about the real cause. “Missing White Woman Syndrome” (MWWS), is a term used to refer to news media engagement focused solely on white women’s disappearances, sex trafficking cases, and kidnappings. The mainstream media releases little to no warning to the nation about the growing numbers of missing and kidnapped WOC due to MWWS.

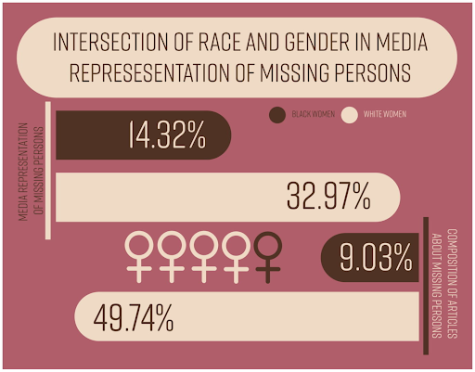

In 2020, approximately 100,000 black women and girls went missing in the United States, although there was no public announcement or national message on the subject. In 2016, a study titled “The Missing White Woman Syndrome,” by law professor Zack Summers found that when black women and girls are missing, the media covers them with fewer stories than other demographics. All of these findings are the result of society’s systematic racism, marginalization, and devaluation of black women and girls.

When national news media mentions missing black women, it is usually because the woman’s family or people who work with organizations dedicated to this issue are bringing mass amounts of attention to the case on social media. Since the early 2000s, social media has been a huge advocate and an important way to spread life-saving information, especially for missing persons.

Historically, American society has humiliated, denied, criminalized, and dehumanized black women of all classes. Black girls are disciplined, expelled, or questioned in disproportionate numbers for their hairstyles, being hyper or happy, disrupting the peace to raise awareness on issues and injustices in society and so much more.

Back in 2019, 12-year-old Zulayka McKinstry was once described as a silly, sociable young girl. This changed when her school principal decided that “hyper and giddy” were suspicious behaviors for a 12-year-old girl. Zulayka was sent to the nurse’s office and forced to undress so that she could be searched for contraband that was never found. In an interview with the New York Times, Ms. McKinstry stated, “It’s not fair that now I have to say, ‘It’s OK to be Black and hyper and giddy,’ that it’s not a crime to smile.”

Events like this place black girls in a box that forces them to abide by society’s norms of how a black girl should behave.

The increase in missing black girls and women and the lack of social awareness about it exposes holes in American democracy, revealing how black women consistently experience moments of fear and silence in their daily lives.

But black women are not the only part of the American population that goes missing with little media representation; Indigenous women also have a large population of missing and murdered women. Organizations like Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women work as a force to fight violence against Indigenous women in Canada, the United States, and Latin America.

Even if you aren’t a regular on news websites or don’t sit down to watch the news every night, you have probably still heard about Gabrielle Petito, the 22-year-old Florida woman who went missing and was later found dead after a road trip with her boyfriend. Petito was a white woman.

In contrast to Petito’s heavy media attention in 2021, you likely never heard about Pepita Redhair, a 27-year-old Navajo woman who’s been missing since March 2020. What about RoyLynn Rides Horse? A 28-year-old died after being beaten, strangled, and set on fire on Montana’s Crow Indian Reservation in 2016. These tragic cases were never seen in the mainstream media because women of color’s cases are not covered with the same level of priority as white women’s cases.

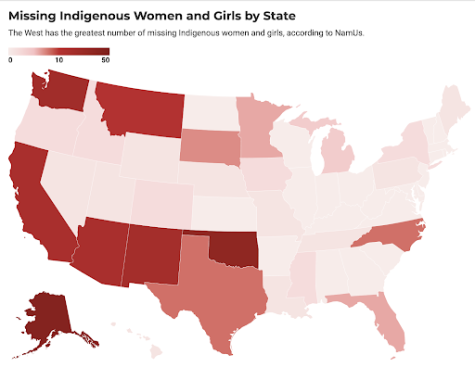

The National Crime Information Center reports that in 2016, there were 5,712 reports of missing American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls, according to the US Department of Justice’s federal missing person database. NamUs (National Missing and Unidentified Persons System) is a national clearinghouse and resource center for missing, unidentified, and unclaimed person cases throughout the United States, only logged 116 cases out of over 5,000 missing Indigenous women and girls in the year 2016. Many missing women and girls were not accounted for, with little to no public announcement or cry for help in finding any of them. To this day, very few of these stories were or have been shared with the public to bring awareness or address the issue by any media center. While indigenous people only take up three percent of the country’s population, they account for 21% of homicide victims.

Thanks to social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok, more information has been spread and made known about what is going on among the Indigenous population in our country.

An article from 2021 highlighted one of the first viral videos produced by a young indigenous woman crying out for help. 2KUTV states “In the short video, MiKayla O’Field of Tulsa, Okla. is seen with paint around her eyes and her hand over her mouth as indigenous music plays in the background. O’Field removes her hand to reveal a red handprint on her face. She then sings “remember me” in harmony with the music.” This video was recorded on May 8, 2020, and its caption reads:

“If you see this, duet. Please spread awareness of the murdered and missing indigenous women. #mmiw #firstnations #native #imstillhere.”

Starting a movement with over 400 million participants, indigenous women from all over the country have demanded the attention of the media.

With recent shows like Alaska Daily, missing and murdered Indigenous women have become a more acknowledged topic in American society. Still, little to nothing is done to bring justice to the families and loved ones of the lost women. However, Colorado’s lawmakers are making positive strides toward bringing justice to its Indigenous residents.

In April, Colorado Senate Bill 22-150 was passed with a 6-1 vote. This act allows Colorado to best serve and seek justice for indigenous persons who have been the victims of violence by establishing an office to serve as a liaison on behalf of missing or murdered indigenous relatives. The act requires the department of public safety to improve the investigation of missing and murdered indigenous relatives cases and address the injustice in the criminal justice system’s response to the cases of missing and murdered indigenous relatives cases states Colorado.gov. While Colorado is taking the first step to lessening the percentage of WOC that go missing and are murdered, many states still lack these types of protectors.

The entertainment industry has also definitely begun to make its stand. A recent show Alaska Daily follows an award-winning investigative journalist, played by Oscar-winner Hilary Swank, who is pushed to leave her high-profile job in New York City behind to join a daily newspaper in Anchorage, Alaska. Swank’s character is assigned to work alongside a young Alaska Native reporter, played by Grace Dove (Secwépemc), to report on the cold cases of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) in the state of Alaska.

Alaska ranks fourth in the nation for the highest number of MMIW cases—behind New Mexico, Washington, and Arizona, according to a 2017 Urban Indian Health Institute study.

As cases rise in America and little to no media coverage is being published and distributed, more and more women of color lose hope for humanity as they feel their presence is ignored and neglected.

Described as passionate and independent, editor Rhyan Herrera has been in Nest Network for three years. After this year, she plans on going to a college...