ILC’s The Place to Be!

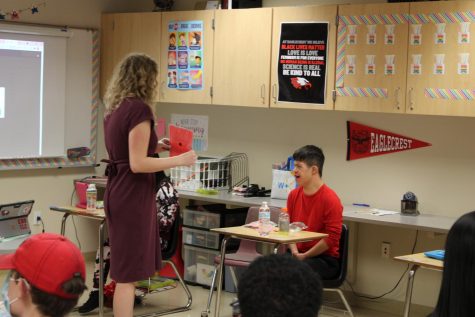

Of the 3000 kids at Eaglecrest, only 44 of them belong in the ILC. Even with such a small population, the class is excited and curious. What do they possibly learn in a day to be such energetic, wonderful students?

One of the many wonders of our high school is the integrated learning center– ILC for short. Since only 1.46% of Eaglecrest’s students are in the program, not many people know about it or what goes on there during the day. But thanks to your tireless friends in the Nest Network, we’re able to uncover the secrets of the ILC.

For someone to qualify for the ILC, they must be in one of Colorado’s 13 disability categories. The categories include: Autism, deaf/blindness, developmental delay, hearing impairment (including deafness), infant toddler with disability, intellectual disability, multiple disability, orthopedic impairment, other health impairment, serious emotional disability, specific learning disability, speech/language impairment, traumatic brain injury, and visual impairment.

The ILC teachers here at Eaglecrest cannot diagnose students with these disabilities; they only help teach students with them. Students who wish to join the ILC must first come to the school saying, for example, ‘we went to the doctor last week and my daughter has severe autism, and she needs to be in this class.’ Along with qualifying for one of the categories above, students must take an IQ test and an adaptive skills test. Adaptive skills include the ability to have appropriate interaction with peers, being able to take care of personal hygiene, or the ability to be independent.

Just like us, the students in the ILC have a block schedule: A day, B day. Their classes are much simpler than a class for an average high school student; they’re less focused on learning subjects like Biology or Human Geography, and more focused on learning life skills and adaptive skills. Many students in the ILC have an intellectual disability which hinders their capacity to have or use these skills. The classes taught in the ILC also focus on repetition and simplicity. Otherwise the class would be too overstimulating for them, giving and or providing too much information at once.

“It’d be like putting a freshman into an AP Economics class, they would have no idea what they’re doing and struggle with understanding the topic, they would get annoyed, and they might start being defiant,” said ILC Teacher Meghan Rietveld. They would end up just failing, and it would be really really hard for them to be in a class that is that much higher than their current intellectual ability.” The same goes for students in the ILC: if the school tries to put them into classes which can not support them where they’re currently at, they won’t learn anything at all, and in school, of course, it’s important to learn. Along with their day-to-day core classes, students from the ILC often go into General Education classes such as Drawing & Painting, Band or other electives.

The ILC also includes two “grade levels”- one for higher functioning students, and one for lower functioning students. The higher functioning students have cognitive abilities similar to the people you see everyday, like a typical high schooler. Lower functioning students are the opposite, they have more severe cognitive disabilities, and thus they must be taught simpler subjects. As is true for many things in the world of disabilities, though, the “lower/higher functioning” system is a spectrum. Someone can be more low-functioning with social aspects of life, while they just can’t read, and that’s why they are in the ILC. There are many different types of students in the ILC, ranging everywhere on the spectrum.

Abigail Lewis teaches the lower functioning students, whereas Meghan Rietveld teaches the higher functioning students. Similarly to elementary school, Lewis teaches all four core subjects to her students, focusing on repetition throughout the school year. “My class does the same thing for math everyday, and we’ll do the same thing for math every single day until the end of the school year,” she stated. “That’s just how long it takes for the kids to understand what’s being presented to them.” In her science class, currently, the students are learning about colors and plants. Rietveld, on the other hand, teaches only social studies and English, and another teacher in the ILC teaches science and math, more similarly to middle school or high school, where subjects are separated by teachers. At Rietveld’s students’ level, they could learn about the states of matter or planets, simply researching them and describing one fact about it for an assignment.

Lewis uses a lot of fun phrases to get her students engaged. When learning the months of the year, she would tell the students to take the laminated paper with the month on it, “raise it in the sky, and let it fly!” The students would raise the papers and wiggle them around happily. When learning the weeks of the day, to change it up, she would use a wheel to choose a student to read filled-in sentence starters, such as “Today is Wednesday”, or “Tomorrow will be Monday”. Compared to the boring lectures of AP US History, the class is extremely entertaining.

After learning about the calendar, they moved onto math, learning simple arithmetic like addition and subtraction, with numbers going up to 20, at this point in the year. Upon being given a problem, students would tell Lewis which number of the two to ‘dot’. For example, if the problem was 20 minus 4, they would dot 20, and ‘jump back’ four, because of the minus. The students would then do the math on a timeline, and hold up the laminated paper with the answer when they were finished. Lewis would call on someone to answer, and that would be that. A bit different from what typical high schoolers would have learned when they were younger; perhaps simplified for the minds of the ILC.

Along with having to teach the students calendar and math, Lewis would have to interrupt class every so often in order to deal with a student in the classroom.

“Sometimes some of our day could be spent helping some students with behaviors. We have students who have some physical aggression, verbal aggression, wandering aimlessly, some who need help with medical needs,” said Rietveld. “So we could spend some of our day either completing those medical needs like toileting and bathrooming or helping feed the students, or just emotional and behavioral regulation, and spend the other part of our day teaching. It’s busy days, I would say, for sure.”

Rietveld advocates for students to be aware of the students in the ILC, whether that be your usage of elevators or even seeing one of their students in the hall. It’s important to treat the students in the ILC just the same as any other high schooler. “When students interact with our kids in any capacity, literally just waving at them in the hallway, they talk about it for three days minimum. So if they want to get to know any of our kids, or get involved in any capacity, it would literally change one of our kids’ whole attitude about their entire day,” she mentioned. Another important point is to ensure kindness to these students. Not only are they the same as any of us, but they’re also our age, and they deserve to be treated that way, not like children.

As Lewis had put it: “They might not necessarily understand everything or they might have a specific interest in a cartoon, but that doesn’t make them much different. You just really have to understand that these kids are your age and you should treat them like any other high school student.” Lastly, when speaking to a student, it’s okay to ask them to repeat themselves, and be patient when they’re trying something. Don’t assume that they need help with something. Instead, just ask! And if you don’t understand them, ask them to repeat themselves! Just as was mentioned before, they are human beings too, they understand that they may slur or speak too quietly, and they understand if someone can’t hear them. And all the same, they are capable of doing tasks, just as you are! Don’t assume they need help unless they ask for it.

In addition to treating the students well, one should treat their equipment well. Rietveld advocates that students should keep things accessible. “I feel like a lot of the time, we’re been struggling with students using the elevator when they don’t need to. The Eaglecrest elevator is literally the slowest elevator in the entire world, sometimes we can be even 15 minutes late to class if someone is messing around in the elevator, because it’s that slow, and there’s only one elevator.” One should not use the elevator if they are capable of walking down or up the stairs- don’t be lazy! There are people in the school who legitimately need to use that equipment. In addition to this, unless it’s a total emergency, don’t use the handicap bathroom! Sure, it’s big and roomy, but in every restroom in the school, there’s only one. There’s a reason why they’re there, just the same as the elevators in the school, and that reason is not for somebody who’s completely able-bodied to use them and take them away from someone who is incapable of doing what an able-bodied person can do. Wait for a smaller stall to open up, and please, use the stairs.

Ren is a senior this year at Eaglecrest. It is their second year as a part of Nest Network, but their first as Magazine Manager. Ren loves writing about...